Why Scientists Should Consider an Entrepreneurial Career

In 2010, I decided not to pursue an academic career, but to become an entrepreneur. And I hope that more academics, PhD students and postdocs will at least seriously consider this career path. However, this blog post is not intended to be a blunt call to action for prospective science founders. Rather, it is intended to provide some ideas and thoughts that might help you make an informed decision.

A key experience for my decision was observing how PIs spent their time. Nils Brose, my PhD supervisor, is one of the smartest people I have ever met in my life. In addition to his intellectual capabilities, he also stood out as a good researcher because he was extremely good at collaborating and disseminating the results of his research. Many conference visits, lectures and partnerships with fellow researchers, and occasionally he wrote an article for a daily newspaper and other media.

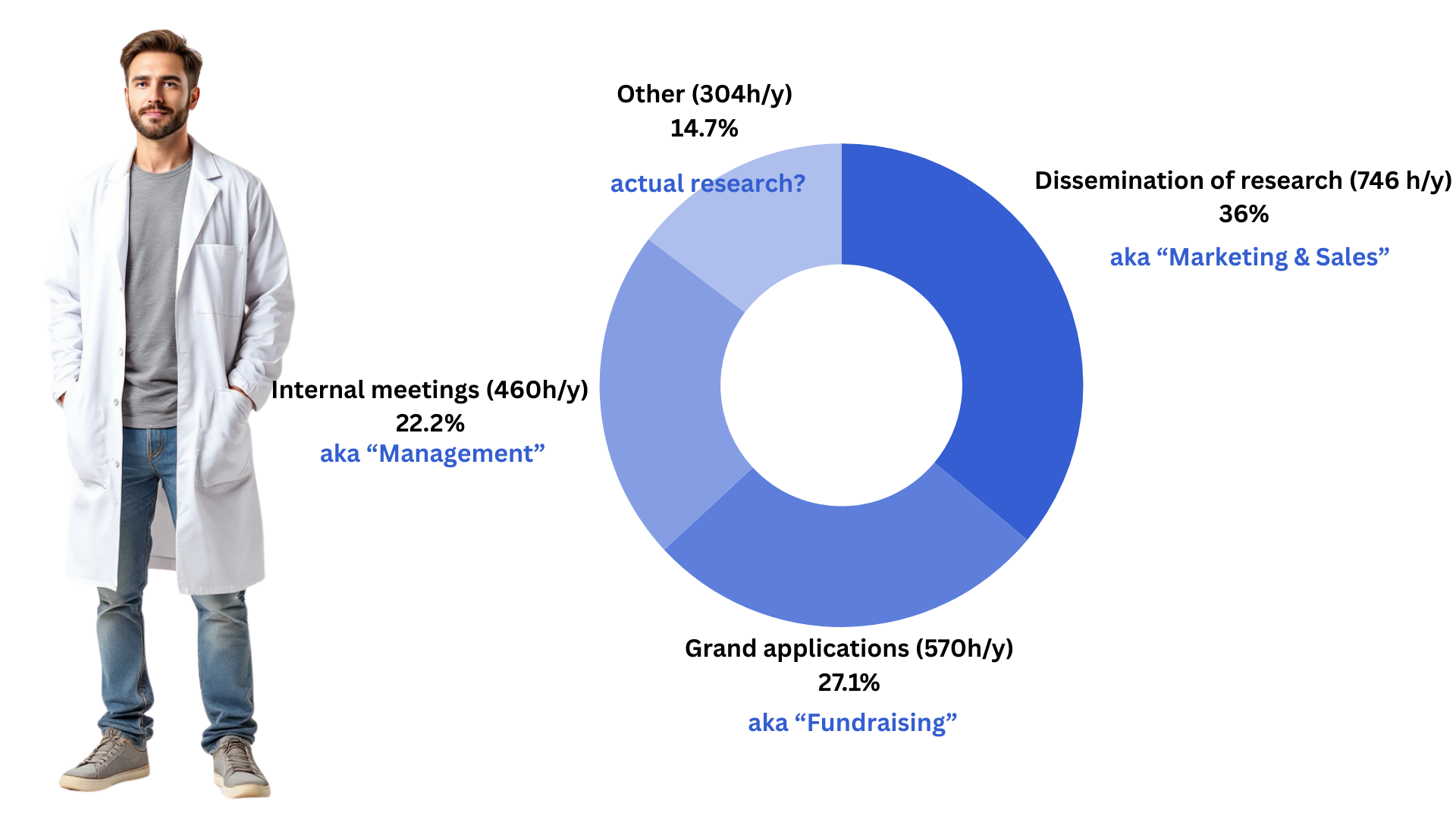

My realization as a young doctoral student was that most PIs no longer spend any time in the lab or doing actual, hands-on research, but all the more time in meetings, on trips, at their desks and, above all, talking about their research. Even if it is often described in academic jargon as "dissemination of research”, to put it bluntly: It’s "marketing and sales" in business jargon. And it’s very important in the life of a researcher! As everywhere else in life, the social component, the ability to network and communicate is at least as important as doing excellent research: Do good... and talk about it!

A decision made instinctively

This realization also gave rise to the idea that life as an entrepreneur is not so different from working as a PI in day-to-day operations. Every founder, no matter how inexperienced, knows by heart that marketing and sales are important. It's essential to talk about your company, your product and your vision!

There were of course many factors that led to my decision to turn my back on an academic career. There were many substantive issues that bothered me about academic research - including topics such as the reproducibility problem (1), bureaucracy and much more. Not to mention: The limited financial development opportunities and the self-critical realization that my scientific skills could never match those of Nils and other top researchers at Max Planck in Göttingen.

So my thought process went something like this: A) if my everyday life is similar in terms of the critical need to do marketing, and B) if my scientific skills are never going to be stellar, while my interpersonal skills are OK, and C) if it's financially more attractive anyway, I might as well go the business route.

However, apart from flea market sales and a few entrepreneurial escapades as a student, I had no idea what to expect from my life as an entrepreneur, so I made the decision instinctively rather than rationally.

I can say one thing up front: I don't regret it.

The decision, rationally considered

However, it is almost part of the professional ethos of scientists to loathe instinctive decisions. So, with hindsight, here's a rational reworking and a few figures for all those who may be facing a similar decision.

I did some research into how Principal Investigators (PIs) spend their time in everyday life and how, in my experience, this relates to everyday life as an entrepreneur.

What do Principal Investigators (PIs) spend their time doing?

Conferences: The marketing channel for science par excellence. According to the literature, "conferences are important activities for networking, collaboration and dissemination of research results" (2). Translated into business terms: This is marketing, sales and business development. PIs travel to conferences to present their research and network, much like CEOs present their products and visions at trade shows and business conferences. Time required: Preparation of content (presentation, poster, etc.): 5-40 hours Logistical preparation (travel planning, bookings etc.): 2-10 hours, conference participation: 24-50 hours, networking and meetings: 5-10 hours, follow-up: 5-10 hours. In total approx. 40-100+ hours, depending on the type of participation and the amount of preparation. So on average 70h per conference. With 1 conference per quarter, that's 280h per year per PI or 13% of total working time.

Other research communication: Platforms such as ResearchGate, the LinkedIn of science, are playing an increasingly important role. This is also about marketing, for scientific projects and expanding networks. There are no exact figures on how much time researchers spend on platforms such as ResearchGate. However, their role in improving scientific communication and expanding collaborative networks is widely recognized (3). ResearchGate, for example, is used by over 20 million users to share and discuss scientific products (4). Using a conservative approach of 1 hour per week per PI, the time spent on scientific social networks and other platforms amounts to approximately 50 h per year per PI.

Reading papers: Translate that into continuous market research and analysis. Again, there are no exact numbers or analysis. An assistant professor stated on Reddit that he reads around 30-50 abstracts and 5-15 of them in full per week (5). I think you have to calculate with 5 minutes per abstract and at least 30 minutes per paper, i.e. around 8 hours per week or 416 hours per year per PI.

In total, marketing & sales as well as market research and analysis come down to around 746 h per year, or around 35% of annual working time.

Grant application: What about applying to grants - fundraising, in business terms? Writing a new grant application can take an average of 38 working days, while resubmitted applications take around 28 days, giving an average of 34 days per application (6) (equivalent to 272h for an 8h working day). Another study involving astronomers and psychologists also found that writing a grant proposal for PIs takes about 116 hours (7). It can therefore be assumed that on average around 190 hours are spent on each funding application.

With 3 research applications per year, this comes down to 570h per year per PI or 27% of the total working time and most of the administrative work (42% total, see above).

What about other activities?

Internal meetings: There are different figures for the exact time spent on internal meetings and unfortunately no specific figures for internal meetings in academic research. On the Internet you can find figures ranging from approx. 7.5% of working time for ordinary employees to 50% for senior management (8). 22% of working time (or around 460h per year per PI, as found in a Swedish survey of inter-professional teams (9), seems to be a good indication.

Summary

How does this relate to the time allocation of an entrepreneur?

In short: very similar. At least in the phase in which you are building a company and assuming that you are an externally-oriented CEO. There are certainly functions in the founding team that are more technically or operationally oriented. But they all have a high marketing & sales share!

In later years, depending on the growth of the company, you will of course be even busier with management tasks and stakeholder management, but in my experience this breakdown is valid for the first few years of a company.

Opportunity & risk, rationally considered

Finally, a few words about opportunity and risk: instinctively, many academics are afraid of failing as entrepreneurs, but rationally, they should probably be more afraid of failing in an academic career:

Only about 15% of all biology PhDs manage to get a permanent position within 6 years (10). A comprehensive study of PhD engineers from 2006 to 2021 found that the average probability of obtaining a permanent position at a faculty is 12.4%. (11).

In contrast, the entrepreneurial career: around 48% of all companies founded in the USA survive the first 6 years (12).

Of course, the fact that a company survives does not necessarily mean that it is doing well. But one thing is clear: the interdisciplinary learning curve that takes place in the first 6 years as an entrepreneur is certainly steeper than in an academic career. At the same time, the financial opportunity is greater.

There is a risk of insolvency, but be careful: this refers to the failure of the company, not personal failure or a total personal financial loss. Provided you proceed with caution, the personal financial risk is quite low in the first 6 years and can be covered (keyword D&O insurance).

On the other hand: After 6 years in academia without a permanent position, the chances of getting a job in industry decrease dramatically, while at the same time the psychological pressure and the feeling of being trapped in academia increases.

From a game theory perspective, the financial opportunity and the interdisciplinary learning curve are higher in an entrepreneurial career. The financial risk may be somewhat higher, but instinctive perception and real risk are far apart.

Ultimately, one career does not exclude the other - provided the hierarchies allow it, you can also pursue an entrepreneurial career alongside your academic career and, conversely, still be connected to the academic world as an entrepreneur, as I was as the founder of Labforward.

Conclusion

I have no regrets about taking the entrepreneurial path.

My hope is that more scientists will also dare to explore this path. The everyday tasks may have different names, but they are similar. Ultimately, it's about looking at the opportunities and risks rationally and not just choosing the supposedly safer option.

To all doctoral students and post-docs who may only be quietly entertaining the idea of setting up a company: It's worth thinking about what you have to gain and what risks you are really taking. The entrepreneurial path is a more than exciting alternative - and one thing is certain: it offers you the chance to use your talents differently and perhaps even celebrate greater success.

References

- Labforward - The Importance of Data Reproducibility. Labforward https://labforward.io/the-importance-of-data-reproducibility/.

- Hauss, K. What are the social and scientific benefits of participating at academic conferences? Insights from a survey among doctoral students and postdocs in Germany. Research Evaluation 30, 1–12 (2021).

- Corvello, V., Chimenti, M., Giglio, C. & Verteramo, S. An Investigation on the Use by Academic Researchers of Knowledge from Scientific Social Networking Sites. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202010.0644.v1 (2020).

- Meijaard, E. & Moqanaki, E. High readership on academic social platforms could poorly reflect conservation interest. Oryx 57, 578–580 (2023).

- tadbafyb. How many papers do you read per week and what is your position in the lab? r/labrats www.reddit.com/r/labrats/comments/7ebwjp/how_many_papers_do_you_read_per_week_and_what_is/ (2017).

- Herbert, D. L., Barnett, A. G., Clarke, P. & Graves, N. On the time spent preparing grant proposals: an observational study of Australian researchers. BMJ Open 3, e002800 (2013).

- Von Hippel, T. & Von Hippel, C. To Apply or Not to Apply: A Survey Analysis of Grant Writing Costs and Benefits. PLoS ONE 10, e0118494 (2015).

- Smith, D. Average Time in Meetings & Its Impact. https://www.flowtrace.co/collaboration-blog/average-time-in-meetings-its-impact (2024).

- Thylefors, I. Does time matter? Exploring the relationship between interdependent teamwork and time allocation in Swedish interprofessional teams. Journal of Interprofessional Care 26, 269–275 (2012).

- PabloAMC 🔸. Estimation of probabilities to get tenure track in academia: baseline and publications during the PhD. (2020).

- Roy, S., Velasco, B. & Edwards, M. A. Competition for engineering tenure-track faculty positions in the United States. PNAS Nexus 3, pgae169 (2024).

- Delfino, D. Percentage of Businesses That Fail. LendingTree https://www.lendingtree.com/business/small/failure-rate/ (2024).